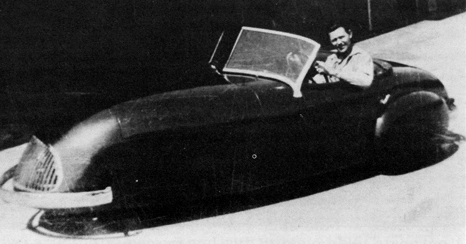

1947 Davis Divan

Country of Origin: USA

Design Info: A three-wheeled roadster consisting of a steel frame, aluminum body panels, and a removable fiberglass roof. The Divan featured all-around disc brakes, hideaway headlights, and built-in hydraulic jacks for easy tire replacement. Its unique styling was loosely based off the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane, and its streamlined body contributed to an impressive fuel economy of up to 50 mpg. Though considered a compact compared to the contemporary American sedans of its time, the Divan was significantly larger than most three-wheeled cars, weighing 2450lbs.

Engine Info: Most Divans were powered by a 2.6 liter inline four manufactured by Continental who built engines for cars through the prewar years but was more known for aircraft engines by the 40s. The engine’s size and position behind the front wheel is partially responsible for the relative large size of the car compared to other three-wheelers. The engine made 63 hp, enough to power the car over 100 mph. A couple prototypes were instead fitted with a 47 hp Hercules industrial engine.

Type: A roadster with a single-row bench seat, the Divan is less like contemporary three-wheeled microcars and more of a personal luxury or even sports car. While it suffered from the inherent instability that all three-wheeled cars with a single front wheel faced, it was said to be fairly sporty, and the car it was based off of, the Californian, was raced in amateur events before its owner sold it to Davis. It is somewhat comparable to cars like the Nash Metropolitan or even the later Hudson Hornet.

History: The history of the Davis Divan begins with none other than Frank Kurtis, founder of Kurtis Kraft and Indy 500 race car builder, who built a three-wheeled roadster in 1941 for wealthy race car driver and millionaire playboy Joel Thorne. This roadster, called the Californian, was driven by Thorne in both amateur races and on the streets of LA. It was there, on the city streets, that a used car dealer named Glen Gordon “Gary” Davis spotted the car, and hatched an idea.

According to some rumors, Gary Davis arranged an opportunity to drive and crash the Californian, lowering its value, and in turn offer Joel a pittance to take it off his hands. Whatever the case may be, Davis successfully purchased the custom car from Thorne for the price of $50. Step one, complete.

Davis then brought the car to the basement of his Hollywood storefront and “hired” a team of aircraft engineers to reverse engineer it into a modern car. At this point, so early into the post-war era, the large manufacturers had only just started building cars again, and for the most part these were almost identical to the pre-war models. Davis saw opportunity to storm the market with a brand new vehicle before the larger companies could update their own lines, and he issued a sort of wager to his new employees: doubled salaries if they succeeded in bringing the car to market, and nothing if they failed.

While his engineers completed a ¼ scale clay model, he toured the country in the Californian, showing it off to drum up interest, and looking for investors. Along with pictures of his model, he made statements to the motoring press suggesting he would before long be producing 50 cars a day at his new factory (a rented airplane hangar) and selling them for $995. He secured his first investor by meeting with the man in an opulent “borrowed” office from a neighboring design firm, and secured $2500 in exchange for the rights to operate a dealership selling Divan cars – the first such exchange of many.

He hired a former reporter as a PR man, and a young actress named Cleo Moore for photoshoots and promotions. He pulled together a production team and supplier staff, and made them all the same deal as his engineers: double pay in the future for successful work now. A successful unveiling to the press, featuring burnouts and donuts on the hangar floor, publicity shots with four American Airlines stewardesses crammed into the bench seat, and lots of free drinks earned plenty of publicity and further dealership sales. Davis eventually raised over $1.2 million in funds by offering dealership rights across the country.

Unfortunately for Davis, this would all come back to bite him. While his workers had produced several fully functional prototypes (including, oddly enough, three military versions), by 1949 there was still no actual car available for sales. For businessmen across the country who had invested in the company specifically for the rights to sell the car, this was unacceptable. Finally, the dealership network crumbled and they sued for breach of contract. Employees quickly followed suite, and the Los Angeles County District Attorney launched a criminal investigation into Davis’s actions. In 1951, Davis would be found guilty of fraud and sentenced to two years at a labor farm, in part due to his inability to pay back the money he owed. He was released after 18 months, on condition that he remain uninvolved in the auto industry going forward.

Davis’s company was liquidated, with the proceeds being used to pay his back taxes. The 13 prototype Divans were given as compensation to some of Gary’s creditors. Of these 13 cars, 12 are still believed to exist in various condition, with the 13th having been destroyed in the UK due to a violation of customs laws. Davis himself died in 1973, maintaining his innocence of any fraud and that he had always intended the Divan to be a real, profitable product.

Why it’s cool/unique/significant: The story of the Davis Divan is not dissimilar to the story of the Tucker 48: Man sees an opportunity to produce an innovative vehicle, challenging the big American manufacturers as they struggle to adapt to the post-war economy, but fails an uphill battle against the difficulties of establishing a large business from scratch. Like Tucker, Davis was charged with fraud that destroyed his reputation and company (though Tucker was acquitted). Like Tucker, Davis believed that at least some of his misfortune was caused by backroom deals between the government and the US Big Three. And like the 48, the Divan was a legitimately innovative vehicle, one deserving of preservation and memory, and one which, frankly, would be very cool to drive.